|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A healthy and beautiful boy. Never before have I been so completely full of love, and never have I felt so strong.

Styrki þig guðir og góðar vættir álfar og dísir og allt sem lifir gróður jarðar og geisli sólar.

These photos were taken in my ninth month. Clever camera angles or straight forward poses could not longer disguise the bump under my dress and my rounder shapes. ^^ This pregnancy has been wonderful, and I have felt so lucky. Not even a single day of morning sickness, but rather an increased appetite and being able to work full-time all the way through. Now it's time to disconnect from that life for a good while, to focus on reovering after a demanding birth process and on my new role. I am now a mother. It feels absolutely surreal, yet at the same time entirely natural, like every woman in my line before me. Music: Wardruna - Bjarkan Poem: Excerpt of Nafngjöf by Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson # Comments

I got a new camera lens for my birthday earlier this month, and I've brought it with me on some my walks in the forest, capturing that early autumn vibe. 📸

The rowanberries, a vitamin boost for the songbirds before winter... Did you know the rowan tree (reynir in Icelandic/Old Norse) is also called Thor's aid, or deliverance? The reason for this is explained in Prose Edda, during one of his confrontations with the jötun Geirröðr and his daughters: When crossing the great river Vimur, the stream rising above his shoulders, Thor gets hold of a rowan branch and pulls himself to land.

I really do love the summer season—especially here in western Norway where we usually don't get too many of those stifling hot days, but rather enjoy that long-awaited green and bright time. But then, there is just something special about this transition to the darker time of year. Knee-high socks and boots, foggy mornings, dark evenings, rainy nights. Is it too early for candles and autumn decorations? I'd say no! 🕯🍂 Music: Anilah - The Loom # Comments

First, some context... Way back in 2012, I attended a local Viking meeting at the farm Spurkeland in Seim owned by Silje and Ole Kristian Kjenes, less than an hour's drive from my home. This was a small and peaceful market with friendly people and many farm animals, including horses that I got to borrow for a ride and an adorable black pig who was sniffling around in the ground of its pigsty. We had a feast in the barn with lots of good food, and I slept on a sheepskin in an open log house with other guests, including my friend Stein Erik and his family. A couple of years later, Stein Erik had gotten a new metal detector, and decided to test it out at the farm. And would you believe it—there he stood, in the middle of that pigsty, holding a tortoise brooch in his hand. To quote his own words from that day:

Can you imagine that? And who was the last person to hold it in their hand? Sometimes, it feels like the history we love is so distant, so far away. But they were people just like us, living right here on the very same land, and we can still literally find things they left behind just a few inches below in the dirt we walk on.

And there were textile fragments there as well. As you may know, natural fibers like wool (and especially plant fibres like linen) can decompose in a matter of months and be completely gone in a few years. This makes textile remains from the Viking Age exceedingly rare compared to more durable materials. Within two days the archaeologists were on site and had gotten funding to start excavations. Among the findings were a couple of tortoise brooches, a trefoil brooch, 24 beads, two iron knives, a spindle whorl and loom weight made of soapstone, and various textile remains. The findings were written up in a report but were not published, as the busy lives of archaeologists and researchers often go. The project leader, Søren Diinhoff, has recently made an important finding at the Ose farm in Ørsta interpreted to be a pagan temple, and is naturally preoccupied with that these days.

My remaining historical wardrobe is mostly based on findings from Birka in Sweden and Hedeby in Viking Age Denmark, but I had never restricted myself to recreate a single grave find. But I was up for the challenge. How often do you come across such a relevant finding so close to home? A project takes shape The Kjenes couple sent me the report they had received after the dig on their farm. I also contacted Diinhoff to ask him more about the project, and whether I was allowed to share contents of the report here on my blog. He has been very helpful and forthcoming, and made my little project possible. According to the report, analyses of the textiles had not yet been performed, but to my surprise Diinhoff later sent me the analysis report for the textiles as well! I was ecstatic. I then got in touch with textile conservator Hana Lukešová who performed the analysis of the textile fragments. She has given me valuable advice and the confirmation I needed to know that I was on the right track in my interpretations of her report. The woman at Spurkeland Based on the grave goods, the buried woman was of some social status. Gilded bronze brooches like the ones found here are however not very rare, but testify to a general wealth among many of the Viking Age farms that were self-owned and where people could afford fine clothing and personal jewelry. The grave was adjacent to a little stone hill that would have created a natural elevation in the area, with a view over the fjord. It was likely covered with a mound of soil making it more visible than what was the case today. Her head and upper body may have been resting on a feather pillow, and a few iron nails suggest a wooden construction (too few for a coffin but probably from a wooden lid over the grave). The different brooches were decorated in the Borre style, placing the finding in the period 850 to 950 CE. The dating is further narrowed down to after year 900 based on their decoration and type, and to the first half of that century based on features among the beads such as the segmented ones visible in the photo above. 🍃The brooches The pair of bronze tortoise brooches found in the grave were double shelled. Each had a gold-plated open-work top shell, richly ornamented with Borre-style masks and grooved lines, and a smooth inner shell. The pins underneath the inner shell were made of iron. They are within type R652/654 (Rygh), categorized as P51 in Petersen's classification of tortoise brooches. When attending historical markets, you will come across smiths who are smelting, forging and working with authentic tools and techniques to make the most astonishingly detailed replicas of historical jewelry. One such talented man is Tomasz from Montanus Historical Jewellery, who made me these beautiful P51 bronze brooches by hand to go with my project. I am so happy with them!

That makes you think, doesn't it? I find it so interesting how these fashion designs managed to find their way to local farmsteads up hill and down dale, in a time where travel was done by foot, horse and ship. 🍃The beads Two dozen beads were found in the area around the brooches. One was a large discoid shaped amber bead measuring 22.6mm, and the remaining 23 were made of glass. For those interested in the details, the glass beads included:

I did not have the beads made to order for this project, but tried to collect similar ones from brilliant vendors of handmade beads such as Hagedisenhain and Nordlys Viking. But recreating the bead row was challenging since it had to be done online, and because this grave find has not been previously recreated. I hope to keep improving it as society and historical markets open up again! The proportions of the individual beads are not correct in all cases either, so if you plan to recreate this finding please feel free to get in touch for the correct measures.

🍃Linen serk (underdress) As mentioned above, findings of textile remains from the Viking Age are relatively rare. Those fragments that do survive have usually done so because they have been in direct contact with metal objects and thus protected by metal corrosion. The location relative to various metal objects such as jewelry, brooches, buttons or tools can often provide clues about the type of garment, and analyses of thread-count and any dyes can indicate its quality and value. Interpreting textile findings therefore requires a lot of just that: interpretation. That was also the case for this finding, we are talking textile dust here, in addition to some decomposed fragments that were up to 2x1,5 cm. Those with an identifiable weave technique were all woven in a plain (tabby) weave. According to Lukešová's interpretations, the fragments stem from three different garments. The first was a linen undergarment—a shirt or a serk, based on fragments of linen found under the tortoise brooch that do not stem from a strap. My reconstruction is handsewn in undyed plain weave linen, and has a rounded neckline. While I usually sew serks with keyhole necklines (to be closed with a small brooch as seen in e.g. several graves at Birka Sweden) these were uncommon in findings here from western Norway. Lukešová believes the neck opening may instead have been a bit larger so that there is room for pulling it over the head without such a slit in the neckline. This is supported by the fact that the trefoil brooch in this grave seems to have been used to fasten an outer layer of wool rather than being attached to the serk. The findings themselves provide little or no clue about the shape of the remainder of the serk, but I made square underarm gussets for better fit and movement (interpretations based on e.g. Skjoldehamn and Birka finds), long sleeves, a single panel for both front and back (no shoulder seam) and two side gores. This is basically a simple and straightforward serk design, made to form a practical and comfortable undergarment without more guesswork than necessary. For further reading about Viking Age underdresses, check out this online article by Thunem.

The second garment in the grave was identified as an apron dress: Underneath the tortoise brooches, there were pieces of both upper and lower straps that very likely belonged to an apron dress. The straps were made of plant fibre (specifically linen), as is most common among findings of such dresses, even when the remainder of the dress is wool. This may be surprising to some readers, since we more often see wool straps on apron dresses among historical reenactors. Apart from the linen loops, the findings do not reveal more details about the apron dress. I therefore based my dress the largest and best-preserved existing find, namely the Hedeby/Haithabu fragment, with a closed and fitted design flaring from the hips and six-strand braids running down along the back. I used blue wool fabric in a plain weave, handsewn with wool thread. This seemed like the most plausible alternative based on previous findings as well as those textile fragments that were indeed found in the grave (see next section).

Finally, the third garment identified in the was an outer layer in terms of a shawl or cloak closed with a trefoil brooch at the neck. The bronze brooch was found in two pieces, and was decorated with three masks facing out toward each lobe with stylized bodies, classified as Petersen's "Norwegian type" P97. I've used my old trefoil brooch here which is not the same design, though also a Norwegian finding decorated with masks. Five of the larger textile fragments were found in relation with the brooch. The weave was unclear, but they were wool, and there was blue dye! The shape of this outer layer is unknown, but I chose to go for a simple "triangular" style shawl in thick wool, which I decorated with blanket stitch along the edges to prevent fraying. As you see in the photo below, the shawl is really a square piece where one corner is folded down and worn at the neck. This interpretation, proposed by Rebecca Lucas, provides a nice shape when draped over the shoulders and fastened at the front, a shape that mimics the profile of shawls commonly seen in Viking Age artwork and Valkyrie pendants. Adjusting how deep the corner is folded allows for the shawl to be pinned at the neck or the chest.

Among the other identifiable objects in the grave were two iron knives (both single-edged and typical for the Viking Age), a loom weight and a spindle whorl both made of soapstone. These refer to the Spurkeland woman's role as a weaver in the household. The production of fine clothes was associated with high status during the Viking Age, and could be a good source of income. The housewife was responsible for the textile production, either as a weaver herself or a leader of weavers in the household, whether they were free people or thralls. One of the unidentifiable tools in the grave may also have been a weaving sword, and there may have been more loom weights. Grave findings of loom weights are however almost never complete sets, indicating that they are symbolic rather than remnants of complete looms being put into the graves. The spindle whorl was unornamented and round with flat parallel sides, 26,4/10,4 mm. Neil from NiddyNoddy UK was kind to make me this one to order, as well as a spindle stick and distaff to go with it (the latter were not found in this grave but are in Oseberg style). All handmade.

I have had so much fun with this project, and feel that I have learned a lot in my attempt to walk in the steps of the woman at Spurkeland. One thing has been in my mind throughout:

I can only hope she would find it exciting. Perhaps she would be willing to teach me how to spin wool like she did? There are so many questions I would like to ask her. But for now it seems we will have to make do with the clues she left behind. To do our best with the existing evidence and the qualified guesswork that is historical reenactment and living history, and to keep aiming to improve.

# Comments

I finally travelled to Iceland again, having spent two years away, the longest I have ever gone without being there.

We had to self-quarantine for half our stay. Luckily that wasn't much of a problem though, since we could live in our cabin at the family farm. There, my grandparents once gave a piece of land to each of their eight children, creating a family village of sorts. And with a "heitur pottur" (hot tub) outside, an unlimited supply of geothermal hot water, and access to all the "hraun" (lava landscape) and mountains above the farm where I could walk for hours without any other people in sight—it was actually nice to spend this time without feeling that we should be out in society doing something. ^^ I rested in the soft moss, sang and practiced the lyrics of Icelandic folk songs, and had fun photographing the odd mushroom, twisted shrub, and lava rock formations here and there. Walking without purpose, not going anywhere.

We were planning to hike to the volcanic eruption site, but had to cancel those plans due to the poisonous gasses at the time. For our next trip I hope to have longer time and opportunity to drive around the country to visit the black beaches, cliffs, waterfalls and other natural wonders of Iceland once again... Do you have a second homeland away from home # Comments

Most people who love living history and staying at Viking and Medieval festivals will know about the feeling of profound longing when a market is over, when people pack up and scatter in their separate directions after having shared days and nights together in a tight-knit community of mutual interests. That post-market blues, that summertime sadness! And when we took down our camp at the last market in 2018, little did we know that would be the last one in such a long time. It has now been two years since we attended my local and favorite market, just ten minutes from home here on the west coast of Norway. But upon hearing that it was postponed again this year, I wasn't having it. The beacons were lit. And Rohan answered! Or at least, everyone in our Viking group Folkvangr did. And after some serious Viking tetris (thoroughly stuffing cars with "necessities" such as meter upon meter of wooden planks and five dresses for a two-night stay) we met for a weekend get-together.

Photoshoot with Silje under the oak trees 🌳🐿

My one & only ♥

Historical tent, based on tent poles found in the Gokstad ship burial. The originals were decorated with black and yellow paint, and unlike them, the carved heads on mine can also be detached during transportation.

Claus, the Dane in our group 🇩🇰 Have I ever told you how I first met him? We were both taking part as extras in a short film for some mutual friends six years ago, in which his part was to slash my throat with his sword... This was avenged shortly after, and we ended up lying "dead" next to each other in the background of the following scenes. And what to do, when you are supposed to lie completely still a few feet apart from your murderer for a good while? You start talking to and getting to know him, and find out he is actually a stand up guy! XD

LC and Benedicte, our camp neighbors with whom Christian and I share this open middle tent. ^^ It provides the perfect shelter for rainy evenings or the burning mid-day sun! This day we had a bit of both, and a rainbow formed above our camp.

Anja by the campfire, which kept us nice and warm all night 🔥

Now I'm back for a few more weeks of work until our summer vacation, and I'm looking forward to see what more adventures this summer might hold 💜🗝🌿 Music: Emian - Dance in circle # Comments

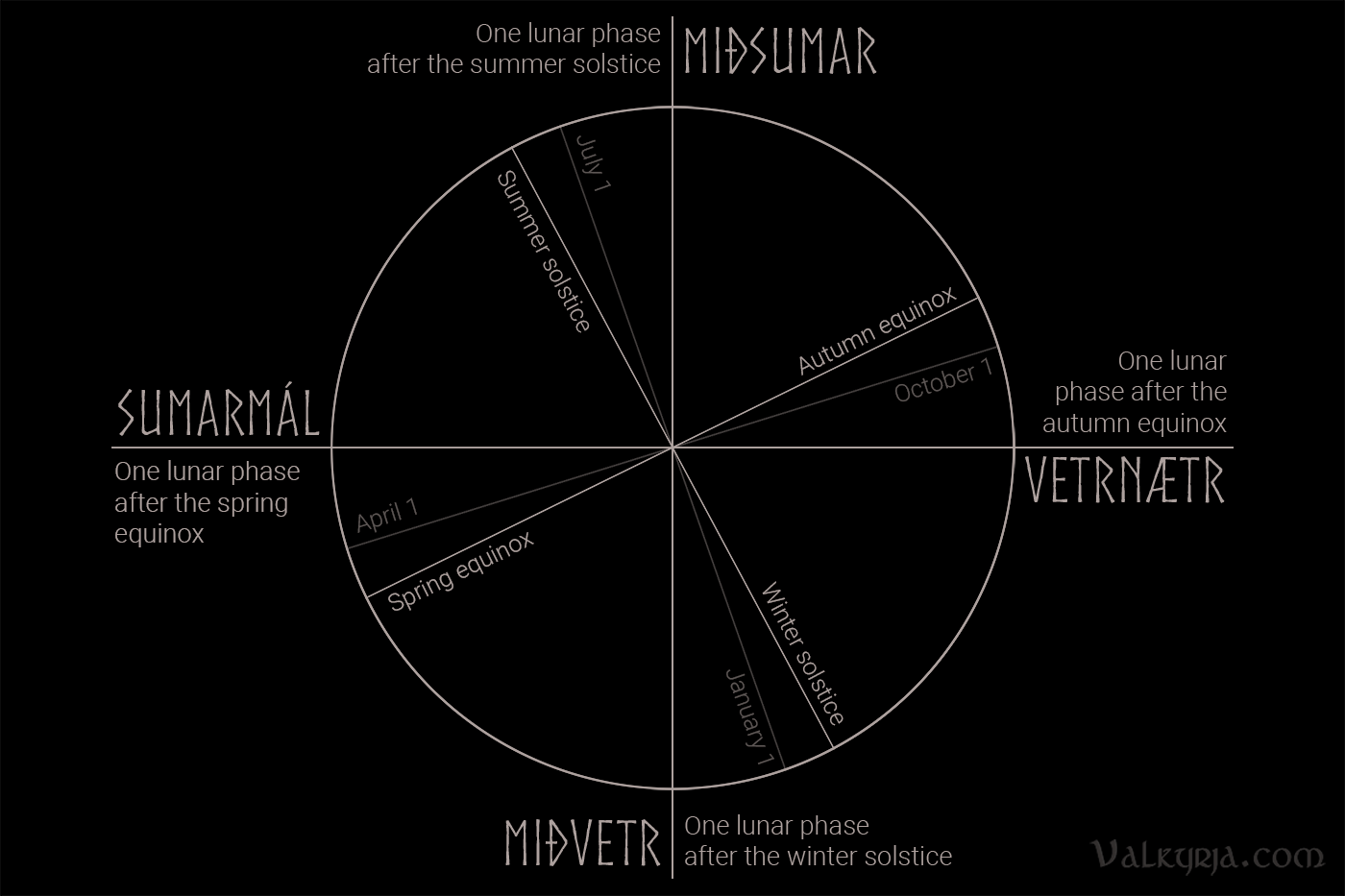

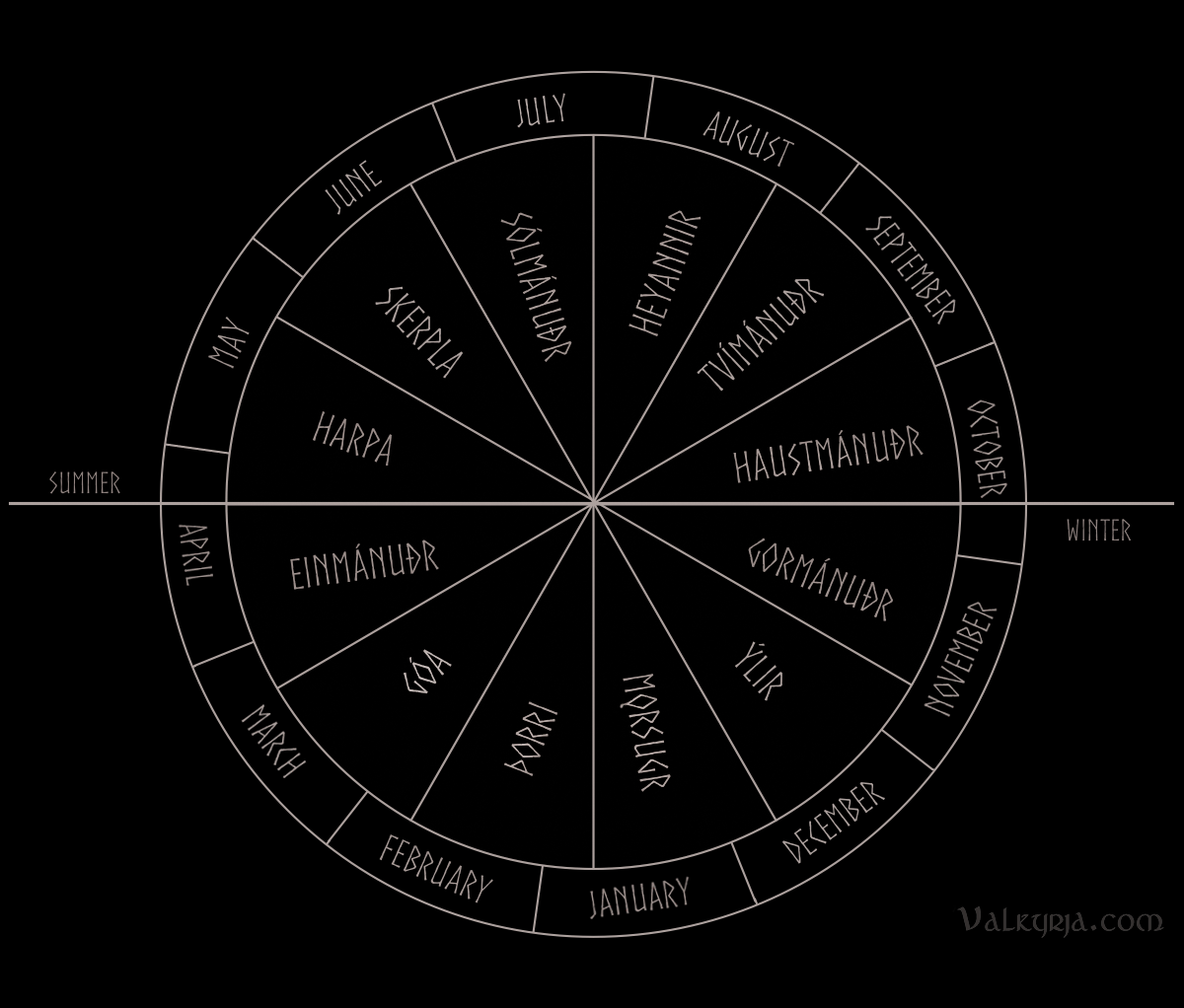

During the Viking Age, the year was divided into two main seasons, summer and winter. Each season consisted of 6 months (lunar phases) each. And according to the Old Norse calendar, we have just entered the third month of the summer half-year. What a great time to be alive! 🌱

But wait a minute... 12 lunar months x 29.5 days. How does that even work? Below is a revised and expanded version of one of my most read blog posts from many years ago, explaining the old calendar and how it is believed to have been used during the Viking Age. Background and context... The evidence base of pre-Christian calendars in the Nordic countries is relatively scarce compared to how much is known about the systems that were adopted with the Christianization. To make matters more difficult, the literature we do have tends to be somewhat conflicting, which makes reconstructing the Old Norse calendar complicated.While this field of research was buzzing in the first half of the 1900s, it lost some relevance after the second world war (1). This left the existing and ambiguous literature unchallenged—until more recent authors picked up the threads and started tying up some loose ends. Notably, Nordberg, a historian of religion, wrote the book "Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning" which provides an extensive overview of information and interpretations (2). The closest we get to contemporary sources are mainly Eddic poetry and various other medieval Icelandic manuscripts from the early 1200s. These provide us with rich descriptions of time-reckoning from a mythological perspective, as well as lists of months and even descriptions of how the year was regulated. But as Nordberg points out, such Nordic evidence is found in contexts where the reader was expected to understand the underlying meaning and expressions used, without needing additional explanations. I think that also helps explain why modern misconceptions about celebrations being centered around the solstices and equinoxes are so common and hard to get rid of, even among those interested in living history: If midwinter/midsummer means the same as winter/summer solstice to the modern reader, they will be happy to assume that the writer of the historical text had the same perspective. The perception that Yule was celebrated at the winter solstice in honor of the sun was a common assumption among researchers from the 17th century that lived on into the 20th century (2), and is still reinforced through popular science articles as well as modern Ásatrú organizations and historical reenactment groups. Many people seem eager to pile Scandinavian religious traditions and feasts into one big pagan sun‑worshipping culture. It does seem intuitive, and it would make it all so much simpler, wouldn't it? But it wouldn't make it any more true. A lunisolar year As mentioned above, the Old Norse calendar was essentially divided into two seasons: the summer and the winter half-year. Each season consisted of six months, or lunar phases, probably counted from new moon to new moon (2).But while there are 365 days in a solar year, a lunar phase consists of about 29,5 days and a lunar year with 12 months will therefore be 11 days shorter. This means that the start of any given lunar month will continuously take place 11 days earlier the year after, causing a displacement in relation to the solar calendar... We see this in purely lunar calendars such as the Islamic one, where the same month occurs in different seasons over the course of the years (2). In geographical areas where the seasons differ significantly, like here in Scandinavia, this would be largely impractical! The names of the Old Norse months indicate a close relation to seasonal changes and tasks in the Viking Age farming society, which further underlines the need for (relatively) fixed months.

This also requires a leap year system. Nordberg describes such a system where a 13th intercalary month was inserted every three years or so. The winter solstice served as the governing time point for this, as it was set to take place in the same month every year. To be precise: If the new moon of the second Yule month took place less that 11 days after the winter solstice, the additional 13th month was added to the following summer, making sure that the new moon month would not occur before the winter solstice in the following year. Medieval Icelandic sources point to another leap year system, but we will get back to that later. The sun and moon in Norse mythology Evidence for the Norse lunisolar year is for example seen in this stanza from Vafþrúðnismál (3) concerning the origin of the sun (sól) and the moon (máni), and how time is measured by their movements over the sky:

Notice the expression ártali—the counter of the years, a term that occurs in several sources where it is also used for the moon specifically. The time period ný ok nið (waxing and waning moon) is furthermore found in sagas and provincial laws as a function to measure time. The beautiful stanzas below from Voluspá (4) describe how the Gods gave the sun and the moon paths and purpose during the creation of the world:

The sun and moon may be envisioned mythologically and iconographically as traveling over the sky in wagons, ships, or by horse (2). In Norse mythology the sun and the moon are pulled across the sky in horse-drawn carriages driven by the personifications Sól and Máni. According to Gylfaginning (5) they were appointed these roles by the Gods as a punishment of their father, and are chased by the wolves Sköll "mockery" and Hati "he who hates". During Ragnarok the wolves will catch up with them and swallow them whole (5, see also 6).

The four quarters and main blóts of the year The natural split between summer and winter as opposing halves is apparent in Medieval sources and can still be seen on Norwegian calendar staffs (the primstav) that have one side for each of the two seasons. But the annual cycle of the year was further broken into quarters, which marked the annual festivals and celebrations (2, 7) or in Old Norse blóts. These were not centered around the solstices and equinoxes, but as we will see, their timing was certainly related to them.The year began with the fall blót during the so-called Vetrarnætr (Winter Nights), at the start of the winter half-year in our present-day October. The Yule blót was held at Miðvetr (Midwinter) in our month of January. The spring blót Sumarmál marked the first days of the summer half-year during our April, and finally the Miðsumar (Midsummer) took place in what is our July. The celebrations seem to have lasted for a three day period, that were later standardized into one day (2, 7). Because of the connection to the full moon, the celebrations were movable. For example, the Yule blót was most likely celebrated at the full moon of the second Yule month. That is, the full moon after the new moon following the winter solstice. The possible interval for this in the modern Gregorian calendar is between Jan 5th at the earliest and Feb 2nd at the latest (this year it was Jan 28, and next year it will be Jan 18th). This coincides with the time for the Yule blót as described in the saga literature (2), celebrated at midwinter, the coldest time of year, not at the winter solstice. The reason for the "skewed" division of the year was probably due to the climatic conditions in the Nordic region, as the warmest and coldest time of year occur later than the solstices and equinoxes.

For more details, check out my separate blog post dedicated to this topic: The four main blóts (feasts) of the year. The names of the months The two main seasons of summer and winter consisted of six months each. The names of the individual months are listed in Medieval Icelandic sources, although many of them are almost certainly much older (2).Rím I from the 1100s and Bókarbót from the 1200s (8) list the six winter months (left column below). Some of the months have complementary or different names that are used in other sources, mainly Skáldskaparmál (10) which also lists the six summer months (listed on the right). A couple of the summer months have additional names that are only attested in more recent sources from the 1600s (Harpa and Skerpla), although it is possible that these also have a much older origin (10).

But why has the knowledge about the winter months been better preserved than the summer months? It might be that the month system was mostly used during the winter half-year, while the work year and its tasks during the summer was more strongly rooted in a week system (2). This could also explain why the names of the summer months have several variations that seem to be local and related to the economic and ecological year, while the winter months seem to be more universal, and to have older names with more abstract or uncertain semantic meaning. Another preserving factor for the names of the winter months may also have been that they coincided with the Christian holidays that were later introduced, which helped ensure their survival. Medieval Icelandic calendar tradition As Christianity came and spread across Scandinavia, the old way of measuring time was replaced by the Julian calendar around the mid 12th century (2). But in Iceland specifically, the Christianization was a peculiar and gradual process (11-13). The old names of the months remained in the Icelandic language much longer, and the Latin names were not adopted into the common tongue until the late 18th century (14).In fact, they still exist to some degree today, much due to their link to folk tales and traditions such as the Þórrablót which is still celebrated across and regardless of religious beliefs. Most modern Icelanders will also know that the men's day is celebrated on the first day of Þorri while the women's day is on the first day of Góa, and the first day of summer remains a public holiday falling on the first day of Harpa. In Medieval Iceland, priests, law-speakers, policy makers and other administrators of the Icelandic society tried to synchronize the different calendar systems that were in use, resulting in a rich material of calendar texts. But this was mingled with basic principles from the Christian church calendar (2), and as a result, it is not clear how this system compares to the pre-Christian system in Iceland. I have drawn it up here as compared to the modern Gregorian calendar (15):

Since that accounts for 360 days, four additional days were added to the third summer month, just before the midsummer. But with 364 days there was still need for a leap year system. So, to make up for the divergence with the solar year, an additional week was added at the end of summer every 7th year, called sumarauki (literally, "summer addition"). This is attested in a paragraph in Íslendingabók (the book of Icelanders) that can be translated to: The wisest men of the country observed from the motion of the sun that the summer moved back towards the spring. But there was no one to tell them that there is one day more in two misseris than you can count using whole weeks, and that was the reason. There was a man called Þorsteinn surtr. When they came to the Althing he walked up to the Law-hill and proposed that to every seventh summer a week should be added, to see how that would work. The proposal was implemented in law. (11).

To sum it all up... In short, the calendar used in Scandinavia during the Viking Age was a lunisolar calendar, where the lunar months were tied to the solar year based on the time of the winter solstice. The solstice thereby served as a governing time point, but apart from that, the solstices and equinoxes did not really have much significance. The year was divided into two main seasons—summer and winter—each containing six months. It was also divided into four quarters, each beginning about one moon phase after the solstices and equinoxes. This was based on the climatic conditions in the Nordic region, and was also the time for the main blóts or celebrations of the year.

References:

Music: Wardruna - Solringen # Comments

Skógarsóley in Icelandic, hvitveis in Norwegian, wood anemone in English. Local botanist Knut Fægri called them the child of the northern forests, and spreading out in blankets across the forest floor long before others wake up from their winter slumber. They say that when it blooms, the goats and sheep can be let out, as indicated by its dialect names such as geitsymre (from Old Norse geit "goat" and sumar "summer"). ^^ I came across my first ones today 🌱

Folk traditions would have you eat the first bud you found in the spring, to protect you from colds for the rest of the year. According to Fægri this might also stem from old fertility rituals, although the wood anemone is actually poisonous.

Come night or rainfall, it bends its head and closes to protect itself from water and cold. They closed during my walk, and sure enough, soon it started to rain. 💚 Music: Encorion - Moonfall, Sunrise # Comments

Embroidery is a somewhat debated issue in the Viking Age reenactor scene. Yes—I am aware that "Vikings" arguing about embroidery sounds kind of funny, but it is true! ^^ The problem is actually a very basic (and presumably also historically accurate) one, namely that many of us like to look and dress nice. But with modern access to an overabundance of fabric, patterns and strong colors, this has a tendency to lead to overdoing things in a way that then tbecomes historically inaccurate. And for many, embroidery in particular has become a pet peeve. This is not to say that embroidery wasn't used in this era at all: For example, we have well-preserved findings of elaborate embroideries on clothing in the Mammen find (1) in Denmark (dated to 970-971). These embroideries depicted leaves, masks, animals and birds, and the yarn contained a lot of iron and copper which may derive from the dyeing process (2). While the surviving textiles consist of silk and wool, many additional needle holes illustrate possible linen embroidery that has since decayed. The same grave contained fragments of dye stuff from Poland or Armenia, tablet weaving of purple silk and silver, fur, golden sequins, and needlebinding in golden and silver threads. The man in this grave (or the people who buried him at the very least) sure knew to appreciate the bling! Other examples are the multicolored embroideries of animals, spirals and geometrical patterns from the Oseberg grave here in Norway—which were possibly made in the British isles (3) and may have been used to decorate the clothing (dated to 834, 4). While we can conclude that embroidery was definitely used during the Viking Age, it would by no means be common in the elaborate way and size of my forecloth which I commissioned from a friend. That piece in particular seems to cause debate when someone posts an old photo of mine in some group on social media such as here, even though I wouldn't have posted it in a group dedicated to historical accuracy myself, or worn in to an event with stricter requirements. Anyway, let's call this "disclaimer" sufficient for now, and on to the topic of my most recent creation that I really want to share with you! I actually made it during my Yule holidays, but due to busy times at work I couldn't get around to posting it earlier. I wanted to try embroidery for the first time myself, and commit to posting it here however crooked and imperfect it might be, so that I will be able to show some progress over the years to come. I chose a pattern based on "the Lady of Tuna", a gilded silver pendant from Sweden dated to the Viking Age (5). She is wearing a shawl over her dress, and a cape with a long train. Her hair (or possibly her haircloth) forms an Irish knot hanging down her back. Some have interpreted the large circles on top of her chest as a possible exaggerated depiction of Freya's necklace Brísingamen, or of a brooch with pearl rows (6).

I used light Icelandic "einband" wool thread for the outline, on pure wool canvas left over from a tunic I made for my loved one a couple of years back. If you follow me on Instagram, you might have seen some of the process: For the filling I used various wool threads that I had lying around from previous sewing projects, including some yarn where I actually had to separate the strands and wax them.

Embroidery done—but what should it decorate? I wanted to make a Birka bag, which is very similar to the Hedeby/Haithabu bag that I've made previously. It's is a clever historical design, where two identical wooden handles shape the bag, and rope is put through holes on each end of the handles to function as a shoulder strap (while also making the bag firmly closed when worn). Many handles for such "bracket purses" have been found in Hedeby, and underwater excavations in 2014 (7) at the harbor in Birka (which was a trading centre in Sweden during the Viking Age) revealed several similar handles but with a somewhat different design. I ordered reconstructions of one of the Birka handles from Taberna Vagantis, and to my pleasant surprise they showed up in my mailbox already a couple of days later. While the handles have been relatively well preserved, less is known about the rest of the bags, how they looked and what they consisted of. The only fabric remaining are some fibers of thread or cord found in the holes in at least one of the brackets from Hedeby, but the bag itself could have been made of cloth, leather, or even some sort of net, as can also be seen in much later iconography of similar bags in Medieval manuscripts (8). I chose to go with wool fabric, and to line it with linen to make it less stretchy.

I wanted to remedy the issues I have experienced when using my previous Hedeby bag, where I have found the opening a bit to narrow, and also to prevent the lumpy look the bag gets when being filled with various stuff. I therefore decided to make side panels in addition to the front and back. All the fabrics are leftovers from previous sewing projects, namely dove blue wool from one of Christian's tunics, blue/grey diamond twill from one of my Hedeby apron dresses, and linen from an underdress.

The final assembled product:

Recent empirical testing (from this weekend) proves that it can comfortably hold my SLR camera, needlebound mittens, and a bottle of mead. ;-) Music: Cornelius Link - Blinding Lights # Comments

According to the Old Norse calendar, we are approaching the end of the third of the six winter months, and find ourselves in the middle of the winter half-year. Next week we will enter the month of Þorri. King Þorri is a personification of winter described in medieval manuscripts such as the Orkneyinga saga. For the past week, we have had lots of wonderful snow here on the west coast of Norway. 🌬

My niece bought me this comb when visiting the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo. ♥

My new Hedeby shoes, handmade by my friend indHans Gunnar at Eikthyrnir. ^^ They are handsewn in vegetable-tanned leather, but modern rubber soles have been added for more durability (and better grip on the slippery snow and grass).

I also made those knee-high needlebound socks recently! Keeping warm and dry. 🧦☝🏻

Music: Munknörr - Andi (ft. Sigurboði) # Comments

Happy new year! A new year, a new and clean page for this year’s posts. As always, the past years posts can be found in the archive links at the very bottom of the blog. And keeping true to traditions, it is time for my annual calendar overview of Viking and Medieval markets in Scandinavia. Side note: Do you know what is a good example of a waste of time? Making my overview for the market season of 2020! Doing the research and finding the proper links, contacting organizers when in doubt about something, and setting it all up—only to have the pandemic hit and the vast majority of markets cancelled a couple of months later. Anyhow, let's not let anything stop us from looking forward to the market season of 2021! This year organizers are understandably more apprehensive about announcing the date of their markets. But while the season might not be a normal one I certainly hope it will be more lively than the last, so that our poor hungry reenactor hearts can find some solace again around campfires across the world. ^^

Some markets are have been cancelled or are biennial/not scheduled for this year (marked as N/A), and as of yet there are also a lot of TBA's (to be announced) which I will fill in as they come. Markets that have fixed dates recurring every year will also be listed as TBA until they have confirmed the actual date for this year. If in doubt about whether an event might be cancelled, contact the respective organizers for more information. (name of event, date, link) in the comment section below. •

🌿 The direct link for bookmarking or sharing this post is Valkyrja.com/calendar2021.html. Music: Kings & Beggars - Como Poden Per Sas Culpas # Comments |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||