|

|

|||||||||||||||||

Myths about Norse cultural history are widespread, often demonstrated by sensational tall-tales from newspaper reports, being quoted and pasted on dubious photos and illustrations shared by the thousands on social media. Be it that "half of the Viking warriors were female" or "why the Vikings were even more savage than you thought", people's concepts of this culture tend to represent either extreme of the scale, with emancipated female warriors strutting around in boob-armor or by chauvinistic mushroom-chewing berserkers trying to rape everything around them. But populist portrayals aside; even when trying to stick to historical sources, we are still likely to run into misinterpretations of archeological evidence, not to mention the fact that historians are basing a lot of their knowledge on medieval literature written by highly biased authors. Sadly, critical examination of sources is often absent in the modern interpretations receiving the most attention by the public. I thought I'd try to write about women in the Viking Age and their role in the society of the time, a good example of a topic that is easily tainted by newer perspectives, possibly leading to prejudice and misattribution of old as well as newer findings. Who were the women of the Viking age?

Firstly, allow me to emphasize that what we call Vikings in terms of conducting overseas raids (excluding overseas trading and colonization), which the modern cliché is based on, may have concerned roughly a half percent of the population (1). But when speaking of the Viking age we are speaking of the whole population, which is an essential difference. Ask yourself; would you feel comfortable being characterized by descriptions of the most extreme individuals of our time?

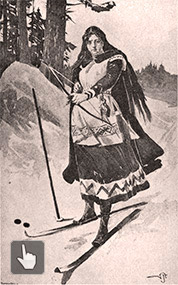

It is common to assume that Viking society was unilaterally male-dominated and that women by definition were suppressed, as humble housewives, browbeaten baby machines or worse. Another common belief is that only the men went Viking so to speak, solely to wage war, plunder and destroy. But research points in the direction of a more egalitarian society, where women enjoyed respect in the community and participated in the emigration alongside their men. As archeologist Marianne Moen suggests in her master's thesis, assuming that men were rated above women in the Viking society is to ascribe modern values to the past, which will be misleading (2, 3). When it comes to religious ideals, the gender culture of Norse mythology was not characterized by Christian women's submission (4), or Islamic women's obedience (5). The historical literature involves clear and repeated accounts of female figures in a broad range of roles; as housewives, priestesses, valkyries, warriors, seeresses and goddesses. It further contains descriptions of heroines, female strategists, travelers and settlers, and there is no reason to ignore these accounts (or to explain them based on these women's association with powerful men), while at the same time accepting descriptions of the male Viking from the same sources. Let me list some further examples of female independence from Norse mythology: In Lokasenna (10), we can read about Freya's father Njörðr, who tells Loki that he should not mind whom a woman chooses to enjoy herself with, or criticize her for it. In Skáldskaparmál (11) we hear of Skaði, who showed up in Ásgarðr wearing a helmet, coat of mail and full armour, to avenge her father. She was granted settlement and compensation, and to choose one of the men in Ásgarðr to be her mate. In Gylfaginning (9) we hear of her following marriage to Njörðr. Njörðr wished to live by the sea, while Skaði wanted to live in the mountains where she could ski and bow hunt. The couple agreed to spend nine nights at a time in each of their dwellings. Eventually Skaði grew tired of the noise of the waves and cries of the seagulls, and moved to the mountains by herself.

When it comes to warfare, strength and other classically masculine or powerful qualities, they were not especially reserved for men—contrary to depiction given by common modern descriptions of Ásatrú. Let me mention Eir (medicine), Hel (death), Frigg (all-knowing), Hlín (protection), Rán (the sea) Snotra (wisdom), Syn (rejection), Þrúðr (strength), not to mention the norns of fate; Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld (past, present and future).

The Valkyries are warrior goddesses, who can ride through the air, and decide the outcome of the war. There are numerous Valkyries mentioned by name, and among them are Hildr who can wake fallen warriors back to life, and Skjeggöld meaning time for the axe. Other examples are Göndul and Skögul, who are described in Hákonarmál (13), when Hákon and his men are dying in battle. They see Göndul, standing there leaning on a spearshaft, surrounded by helmet wearing women sitting tall on their horses. The Valkyries chose who would live or die in battle, and brought them to Ásgarðr. Of all the warriors, Freyja chose half to bring to her domain Folkvangr, while the rest went to Óðinn in Valhöll (Valhalla) (9). Long before the Viking Age, there was the 9000 year old skeleton from Bäckaskog (17), who was buried with a spear and chisel, called the oldest hunter in Scandinavia, and assumed to be a man. Later investigations showed that the hunter had given birth to 10-12 children. Examples of archeological findings where women have been misidentified as men based on the items located in the grave, such as swords and armor, are also seen among Viking Age grave findings. Later studies of skeletal remains at Repton Woods in East-England have revealed that nearly half of the remains were female (18). Although the implications of that particular finding have been exaggerated out of proportion by popular media (who are unlikely to have accessed the original report at all), it does give reason to believe that other graves where it has not been possible to determine gender, but where the assessment has been based on such objects, may be subject to possible bias and gender prejudice. Research shows that women took large part in the emigration to England, even in the earliest periods (18). Whether they came as warriors, tradeswomen or family members, the collective evidence of the literature, mythology, archeology and legislation of the time does cast doubt about the assumption of the Viking age as a tendentious era consisting of dominant machomen, with females as passive housewives and shadows in the background. One can assume that gender roles in the Viking Age were most certainly practically distributed considering childbearing, mobility, physical abilities and age—but there is no indication that these limits were rigid and without room for individual variation, or that one gender was deemed more honorable than the other. The understanding of the Vikings as primarily being farmers and traders often comes short when competing with dramatic stories or television adaptions of bloodthirsty warriors and raiders. We know that the Vikings were responsible for pillaging (just like Franks, Anglo-Saxons and Arabians also were) but it is important to remember that these events were documented by Christian scholars and literate men of the time, who surely had religious and political reasons to avoid understatements. As Torgrim Titlestad (19) puts it: The Vikings appearance in Europe was described by terrified and propagandizing Christian monks, who often concealed abuse and cruelties undertaken by their own rulers. When it comes to the stories of sexual violence which are so often referred to, these are not rooted in the written sources, as opposed to accounts of that carried out by other groups of the same time (20).

Now, you can of course accuse me of being naïve and uncritical, and say that this blog post is my interpretation based on wishful thinking of the horrible things committed by the Vikings not taking place. But I firmly believe that if you—completely devoid of contemporary gender roles—look at what we can actually claim to know based on tangible and evidence-based research findings, the Viking age was probably a much less stereotypical and male-chauvinistic society than what is the general perception of this people today.

Photography: Thomas Lekfeldt and Silje Samdal # Comments |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||